Complicating PAYE Settlement Agreements

Justine Riccomini and Joanne Walker explain the implications of partially devolving income tax to Scotland and Wales for UK employers when preparing PSAs

Key Points

What is the issue?

Income tax has been partially devolved to Scotland since April 2016 and to Wales since April 2019. This can create complexity for employers using PAYE Settlement Agreements, where they have employees resident in more than one UK jurisdiction.

What does it mean for me?

It is important for employers to identify carefully employees to whom PAYE Settlement Agreements apply and their tax status, so that they can calculate their tax and NIC liability correctly.

What can I take away?

How to ensure employers and payroll providers calculate tax and NIC liabilities correctly in respect of PAYE Settlement Agreements.

PAYE Settlement Agreements (PSAs) were first introduced in 1996 to replace the non-statutory ‘voluntary agreements’ which employers could agree with their local PAYE inspector at the tax district. The original method was used as an administrative easement for employers that wished to settle the tax liability of their employees for items which would otherwise have to be declared on Form P11D as benefits in kind, or payrolled. Typically, items which could be settled with HMRC were staff entertaining, achievement related rewards, and gifts.

These arrangements worked well for some employers but not for others due to their informality.

This situation gave rise to the PSA, which was placed on a statutory footing under what is now ITEPA 2003 ss 703 to 707 and the Income Tax (PAYE) Regulations 2003 Reg 105, which require the employer to agree to become liable for the income tax due on amounts which are otherwise chargeable on the employee. The National Insurance legislation at Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act (SSCBA) 1992 s 10A prescribes the Class 1B employer’s NICs liability on benefits included in a PSA which was introduced from 6 April 1999.

PSAs were renewable annually. Employers had to sign up to the PSA using Form P626 prior to the P11D submission deadline of 6 July following the tax year in which the payments were made.

The benefits in kind which could be included in a PSA had to fall into all the following categories to qualify for inclusion:

- Minor: not substantial in nature, but not items qualifying as trivial benefits, which are exempt;

- Irregular: not expected by way of the employment contract and not paid at regular intervals; and

- Impracticable: not possible to apportion between beneficiaries or difficult to value.

Items such as beneficial loans, company cars, bonuses and round sum allowances were specifically excluded from inclusion in a PSA under the legislation.

Items which can typically be included in a PSA

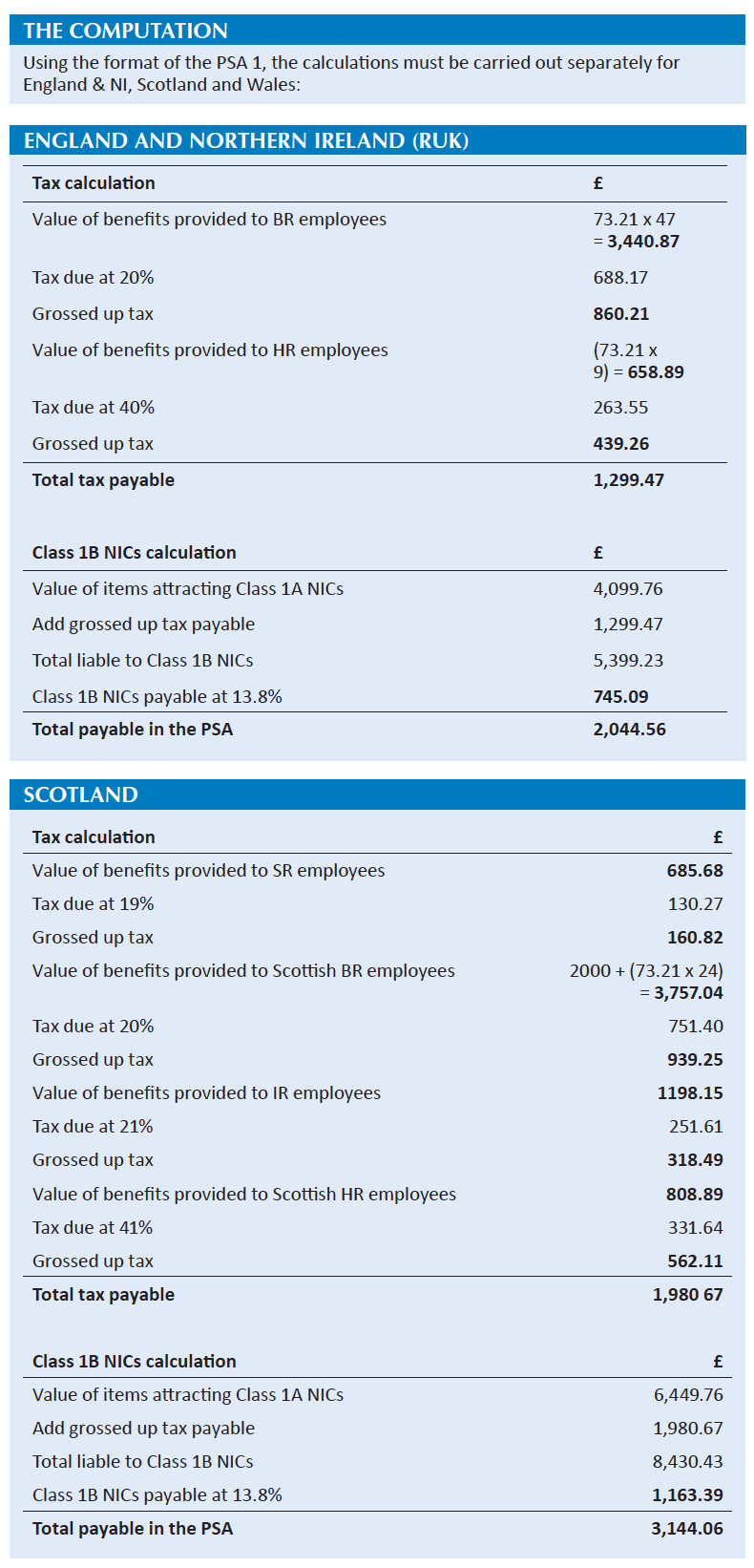

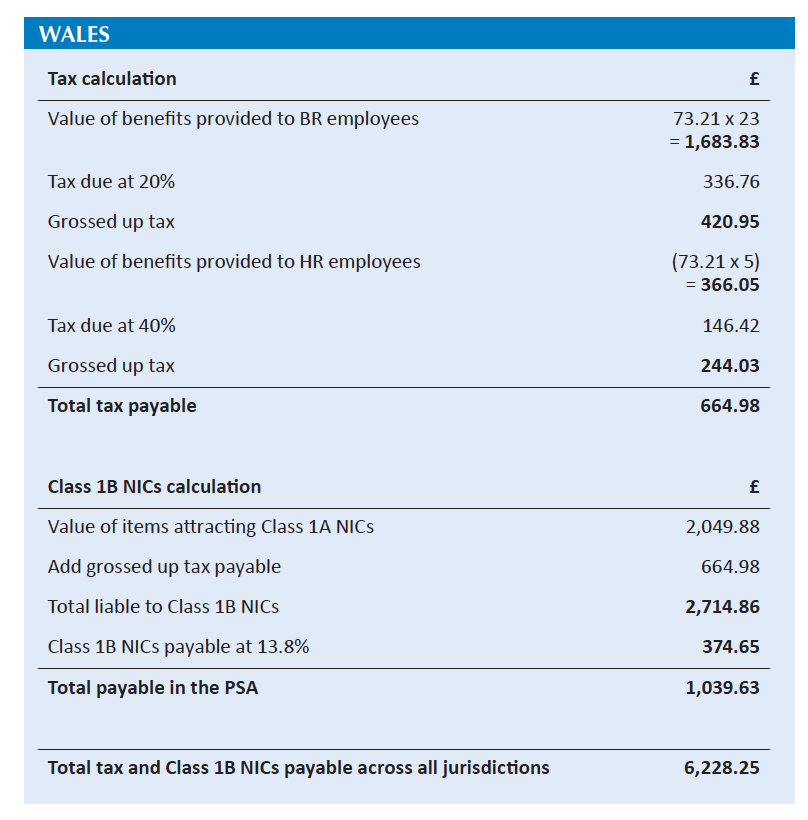

Calculating and paying the tax payable Regulation 108 of the PAYE Regulations sets out how the tax liability on the benefits should be calculated, requiring only that the number of employees in receipt of qualifying benefits within each marginal rate tax banding be used to compute the liability.

Prior to partial devolution of income tax to Scotland in April 2016, no individual calculations or exact figures were required – it was sufficient to say, for example, that a benefit of £300,000 had been provided, and that approximately 20% of the recipients were higher rate taxpayers, the remainder being basic rate. This was a relatively simple way for employers to pay over what was due and proved successful at generating revenues. If an employer is certain that they do not have any employees who are Scottish or Welsh taxpayers (see below), this remains true.

The PSA liability is calculated using a prescribed Form PSA1. This is generally requested by HMRC to be sent in and agreed over the course of July

and August, so that the liability can be settled by 19 October (postal payments) or 22 October (electronic payments) following the tax year in which the benefits were provided. Note that for higher and additional rate (top rate in Scotland) taxpayers, settling the tax and NICs using a PSA can be expensive due to the grossing up process, which can almost double the cost of providing the original benefit.

Reviews and changes

Almost 20 years after the introduction of the PSA, in 2014 the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) carried out a review of employee benefits and expenses. It concluded in its (second) 2014 report that any benefit in kind of any value should be capable of being included in a PSA; and also that the PSA annual renewal process should be abolished as it was time consuming and largely unnecessary. The government accepted the latter recommendation but not the former, saying that it would keep this under review.

HMRC launched a consultati on in August 2016, following which some revisions were made to the PSA process. The main change from 2018/ 19 onwards was that PSAs are now an ‘enduring agreement’; i.e. they do not need to be renewed each year for as long as they are needed or unless HMRC cancels them. Changes made to the benefits listed will require a new agreement.

Partial devolution of income tax powers in a PSA context

The ongoing devolution programme of taxes within the UK from Westminster to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (NI) has to date included the partial devolution of income tax to Scotland and Wales from 2016 and 2019 respectively. Income tax rates have not been devolved to NI.

As far as the partial devolution of income tax to Scotland goes, under the Scotland Act 1998 as amended by the Scotland Act 2016, Scotland now has powers over the rates and bands of Scottish income tax. The Wales Act 2014 provides powers over income tax rates of Welsh income tax. Both Scottish and Welsh income tax is chargeable on income defined as ‘non-savings, non-dividend’ income; broadly, this includes employment income, self-employment profits, pension income and income from property received by those qualifying as Scottish or Welsh taxpayers in a tax year.

"It is in the interests of both Scotland and Wales to ensure that income tax receipts are maximised"

It is in the interests of both Scotland and Wales to ensure that income tax receipts are maximised to fund public services in those jurisdictions. In this context, it is vital that PSA calculations are performed as accurately as possible depending on the residential status of the employees. From April 2016, employers should have been calculating the portion of the PSA which applies to Scottish taxpayers using Scottish income tax rates (and bands from April 2017). If the employer has employees who reside in Scotland for tax purposes as well as employees resident in the rest of the UK, two separate PSA computations should be set out – one for Scottish taxpayers and the other for Rest of UK (RUK) taxpayers.

In Wales, the Welsh rate of income tax applies from 2019/ 20 but it was not varied from that of the rest of the UK. However, HMRC has stated in its October 2019 Employer Bulletin that a separate computation for Welsh taxpayers is required to be set out in the same way as employers already have to do for Scottish taxpayers.

The instruction in the Employer Bulletin is to identify employees by way of their tax code; i.e. Scottish taxpayers are identified by an S prefix and Welsh by a C (Cymru) prefix. This means that employers will need to monitor the provision of all benefits in kind designated for PSA inclusion by jurisdiction from the beginning of each tax year and identify all the employees in that jurisdiction by tax band. Different PSA1 forms are available for each jurisdiction to be completed online.

There is no legislative requirement for employees to be included by name in the actual PSA computation but it would be wise to ensure that a robust audit trail for this process is in place to defend the accuracy of the computations and to ensure that each country is receiving its respective devolved funding.

It should also be noted that individuals are Scottish (or Welsh) taxpayers for a full tax year. Therefore, if the code prefix changes mid-year because someone has moved, then it is generally the year-end code prefix that should be followed, as this should reflect the status of the individual for the tax year. Employers may wish to check the position with employees whose code prefix has changed during the year prior to finalising the PSA(s) for that tax year.

Conclusion

The simplified process for performing PSA calculations has become more complicated due to devolution. Employers now need to keep more detailed records than ever before in order to ensure that the tax liability is correct and the funding reaches the right jurisdiction. Care and attention to detail are required.