LITRG Budget representations

LITRG submitted a Budget representation building on LITRG’s ongoing work on how pensions tax relief might be equalised for all low-income workers and a representation on the high-income child benefit charge.

Pensions tax relief: low-income workers

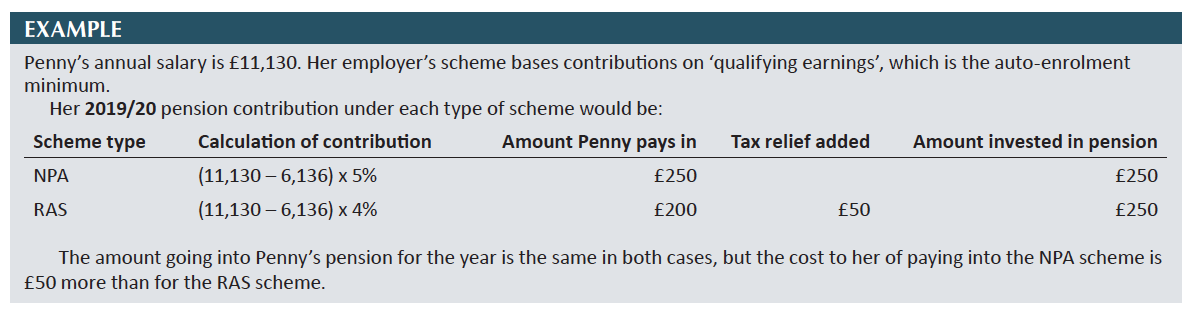

In September 2018’s Technical Newsdesk, LITRG’s Meredith McCammond reported on our work to investigate how tax relief might be given to all low-income workers, irrespective of whether their employer’s scheme operates on a net pay arrangement (NPA) or relief at source (RAS) basis.

To recap, those workers earning around or beneath the personal allowance who contribute to an NPA pension scheme will not receive the tax relief that they otherwise would if their employer’s scheme ran on a RAS basis. Under NPA, contributions are deducted from gross pay and income tax is then calculated

– so someone already earning beneath the personal allowance will get no tax relief. By contrast, under a RAS scheme, the net-of-basic-rate tax amount is deducted from net pay after tax and the pension scheme then reclaims tax at the basic rate – meaning that even non-taxpayers get the benefit of basic rate relief. The net pay contributors will therefore pay up to 25% more for their pension contributions.

This has always been a problem, but it now affects increasing numbers due to pension auto-enrolment, with many schemes used to deliver auto-enrolment operating on an NPA basis.

Employers must automatically enrol qualifying staff into a pension scheme when they earn over £10,000 a year. Automatically enrolled staff may opt out, but opt out rates remain low. Staff not eligible to be automatically enrolled may opt in, or join, their employer’s scheme. The worker usually has to contribute 5% of their ‘qualifying earnings’, from £118 up to £962 per week for 2019/20. (See box below.)

It is estimated that this flaw in the rules means around 1.75 million low-income workers earning below or just above the personal income tax allowance (mostly women) are being unfairly charged 25% more for their pensions as a result of the way their employer pension scheme operates.

LITRG has been working with a coalition of other interested parties – the Net Pay Action Group, made up of pension providers, lawyers, tax specialists, payroll specialists, employers, consumer groups and policy experts – to look at potential solutions to this issue.

A welcome step forward was that the 2019 General Election Conservative manifesto stated:

‘A number of workers, disproportionately women, who earn between £10,000 and £12,500 have been missing out on pension benefits because of a loophole affecting people with net pay pension schemes. We will conduct a comprehensive review to look at how to fix this issue.’

In its Budget representation, the Net Pay Action Group is calling on the government to take forward the promised review as soon as possible and that the upcoming Budget will be an opportunity to provide an update on how addressing this issue will be taken forward. We would like the government to provide a firm timeline for its pledged review of the system and commit to implementing a solution. The representation urges the government to consider the action group’s proposed solution of a system that would allow HMRC to identify which savers, earning below the income tax threshold, have contributed to a net pay scheme. HMRC could then provide that government savings incentive, worth 25% of each low-paid worker’s pension contribution, through an existing process.

The representation can be found here: www.litrg.org.uk/ref375.

High-income child benefit charge (HICBC)

The HICBC was introduced in January 2013, imposing an income tax charge to claw back child benefit where the claimant or their partner has adjusted net income in excess of £50,000. The HICBC has been a controversial policy since its introduction. Questions have been raised about the fairness of the policy and whether it is cost effective. For these reasons, we think it is sensible for a review of the policy to be carried out to assess if it is working as intended and whether it meets its original objectives.

First, some families affected think that making a child benefit claim is not worthwhile if it will be clawed back in full (or even in part) via the tax charge, especially given the fact that liability to the HICBC requires the completion of a self-assessment tax return. But not to claim the child benefit in this scenario carries unforeseen consequences for the would-be claimant, as they might miss out on National Insurance (NI) credits for up to 12 years (or potentially longer if there is more than one child in respect of whom child benefit may be claimed). This could have a serious impact on their future state pension entitlement. LITRG endorses the following recommendations made by the Office of Tax Simplification in their report, Taxation and life events, that: ‘The government should review the administrative arrangements linked to the operation of child benefit, making clear the consequences of not claiming the benefit, with a view to ensuring that people cannot lose out on national insurance entitlements.’ It also stated: ‘The government should consider the potential for enabling national insurance credits to be restored to those people who have lost out through not claiming child benefit.’ LITRG recommend that the government should allow claims for national insurance credits for years where a person (or their partner) would have been entitled to child benefit and they (or their partner) had adjusted net income over the HICBC threshold. There should be no time limit for such claims.

Second, given that the £50,000 threshold has remained static since the charge was introduced in 2013, it is affecting an increasing number of families. We therefore suggest that the £50,000 threshold should be uprated to £60,000 in order to minimise the impact of the charge and to ensure the policy works in the way originally intended. Thereafter, the threshold should be reviewed regularly, or preferably provision made to automatically uprate it annually in line with inflation.

Third, there is a particular issue which affects families in which child benefit is claimed where the higher income partner has adjusted net income of between £50,000 and £60,000 a year: the effective marginal rate applicable to that person. This is exacerbated when there are large numbers of children involved, which is not uncommon in families of certain origin, and so may be said to be discriminatory. For these families, finances are already likely to be stretched. Accordingly, we recommend that the point at which child benefit is fully withdrawn should be increased from £60,000 to at least £75,000. Alternatively, the child benefit could be withdrawn instead by a fixed amount for each £100 above the initial threshold, rather than a percentage of the total child benefit received.

The representation can be found here: www.litrg.org.uk/ref374.

Kelly Sizer

[email protected]