Taking the credit

Kathie Haunton and Sarah Goodman explain the practical considerations of claiming the research and development expenditure credit

Key Points

What is the issue?

Since the introduction of the RDEC in April 2013, claimants are beginning to understand the practical implications and issues arising from the workings of the regime

What does it mean for me?

Submitting an RDEC claim has an impact on both the tax computation and the statutory accounts. Claimants need to be aware of the practical implications for the company’s management, the need to track additional tax entries and the adverse cash flow position

What can I take away?

Practical insight of the key points to consider in order to manage the full process associated with an RDEC claim

The research and development expenditure credit (RDEC) was introduced by the Finance Act 2013 and has led to a change in how research and development (R&D) tax relief can be claimed by large companies and, in some circumstances, by SMEs. Two years into the new regime, companies and their advisers are beginning to fully understand the wider implications of claiming the relief. For those claimants yet to elect into the regime, there is an opportunity to learn from others before the rules become mandatory from 1 April 2016.

Background – recap of the regime

The RDEC rules have been inserted into CTA 2009 Ch 6A Pt 3 and claims can be made for R&D expenditure incurred by large companies on or after 1 April 2013. The regime is also applicable to funded or subsidised R&D expenditure incurred by SMEs in the same way the existing large company super-deduction regime can be claimed for such costs. The relief has been structured to allow the credit to be recognised ‘above the line’, most likely as either ‘grant’ or ‘other’ income, in the company’s financial statements. This means that the credit increases profit before tax (PBT) and so is more visible to a company’s stakeholders.

RDEC continues to use the guidelines produced by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills to define the activities that constitute R&D, and applies to the same categories of qualifying expenditure as the historic large company regime. A project is therefore eligible for relief when it seeks to achieve an advance in science or technology and, in doing so, the project is looking to overcome a scientific or technological uncertainty. Revenue expenditure on staff costs, software or consumable items, externally provided workers, payments to the subject of a clinical trial, qualifying expenditure on contracted out R&D and contributions to independent R&D that relate to eligible R&D projects can all qualify as before.

So what’s different?

Initially, the RDEC was introduced as a taxable credit calculated as 10% of a company’s qualifying R&D revenue spend incurred on or after 1 April 2013. As part of the government’s policy to further incentivise R&D in the UK, the rate was increased to 11% for expenditure incurred on or after 1 April 2015. For taxpaying companies, the RDEC benefit reduces the claimant company’s corporation tax liability. Since the credit is taxable, the net saving is 8.8% of the qualifying R&D spend, providing an extra 2.8% of relief when compared with claiming the existing super-deduction of 130% (assuming a main rate of corporation tax of 20%) as illustrated in Table 1.

For the first time since R&D relief was introduced for large companies in 2002, there is also the opportunity for large (non-SME) loss-makers to claim the credit, net of a notional tax charge calculated at the current rate of corporation tax, as a cash receipt from HMRC. This means that the RDEC will be of monetary value to claimants irrespective of their tax position. The notional tax deducted can be surrendered to another group company that has a corporation tax liability against which it can be offset, or carried forward for offset against future corporation tax liabilities.

The payment of the cash credit is, however, subject to a cap based on the PAYE and NI paid to HMRC for staff whose costs are included in the RDEC claim. The cap has been designed to avoid cash claims being paid out where there is no significant UK presence, and is in practice unlikely to affect a significant number of companies. Amounts in excess of the cap can be carried forward for use in future periods.

Any value remaining after the notional tax deduction and the PAYE/NI cap can then be used to discharge a corporation tax liability of the claimant company for any other accounting period. Any amount remaining can be surrendered to another member of the group, subject to a number of provisions around overlapping accounting periods that operate much as the group relief rules.

As with the SME regime, there is also a provision to extinguish the credit if the company was not a going when it claimed the relief.

The RDEC delivers a greater monetary benefit than the historic super-deduction regime as illustrated in Table 1.

The RDEC and the large company super-deduction regime will co-exist until 31 March 2016, when the latter will cease. Before then the super-deduction is the default position, but companies can choose to adopt the RDEC by entering into an irrevocable election.

The greater monetary benefit and opportunity for loss makers to claim a cash credit are both value-enhancing changes, but not all companies are making the election because there are practical issues to consider.

Practical issues

Management information

The RDEC regime was drafted to have the attributes of a grant so that it could be accounted for in profit before tax, rather than as part of the tax charge. This means that the RDEC credit has been ‘decoupled’ from the calculation of a company’s tax liability and does not appear within the taxation line in the financial statements (although the tax charge will be increased by 20% of the credit since it is a taxable amount). Common practice is to record the credit as either grant income or other income in the profit and loss account but the precise treatment will need to be agreed with the company’s auditors.

Although this treatment has a positive impact on PBT, it does cause an increase in the effective tax rate (ETR). Using the figures in Table 1 and disregarding any other permanent or temporary timing differences, the tax charge after claiming the super-deduction is £140,000 on a PBT of £1 million (an ETR of 14%), whereas when claiming RDEC, the tax charge is £222,000 on a PBT of £1,110,000 (an ETR of 20%).

Also, during the three-year period when claiming RDEC is optional, there can be an issue with claiming foreign tax credits. This occurs if the claimant company is a subsidiary in a US-headquartered group because it will be considered to have elected to pay a higher tax charge than would not otherwise have been the case.

Finance teams may wish to reflect the RDEC in the monthly management accounts to capture the impact on financial measures such as earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) and the ETR. If monthly estimates are required, a process will need to be developed to capture the information and may sometimes involve the participation of employees outside the finance department to determine the eligible activities.

The RDEC claim can be a difficult number to budget for and may not have been included previously in the management accounts or reported to the board, since any historic R&D claims will have been accounted for in the tax expense. The challenge is to set up processes to capture and analyse the information without the exercise becoming burdensome. Many companies have already been requested by HMRC to introduce contemporaneous time recordings. Although this can sound onerous, taking steps each week or month to identify eligible projects and the time spent on them will provide companies with the information to prepare robust estimates. At the same time HMRC’s increasing desire for more contemporaneous analysis will be met.

Tracking the credit

An estimated RDEC claim amount is often recorded in the statutory accounts because they may need to be finalised before the work to calculate the actual amount has been completed. In the early years of RDEC a company may file its accounts with no RDEC included at all if, for example, the decision as to whether to claim it had not been made when the accounts were finalised. In the tax computation, however, the finalised claim must be included and any differences, together with any adjustments made due to HMRC enquiries, can lead to reconciliation between the RDEC figure in the statutory accounts and that in the tax computation.

Further adjustments to reflect RDEC costs included in intangibles for accounting purposes and reversing the associated amortisation can lead to an even more complex position. It is therefore vital that companies track the details of the RDEC entries each year to ensure that the credit has been taxed only once in the company’s tax return.

Let’s take the example of a first-time RDEC claimant with the fact pattern shown in Table 2.

At the time the company identifies that it is eligible to make an RDEC claim, its statutory accounts for the year ended 31 March 2014 have already been filed at Companies House. Consequently, the credit income relating to the RDEC of £100,000 has not been reflected in the statutory accounts. When the tax computation is prepared it will be necessary to make an adjustment to profit before tax to reflect the additional RDEC income of £100,000.

This will increase taxable profits by £100,000 and in turn, the company’s tax liability by £23,000 (assuming a main rate of corporation tax of 23%), delivering a net benefit to the company of £77,000. In year two (APE 31 March 2015), the company will record £250,000 of income to its profit and loss account to reflect the £100,000 RDEC for the year before, as well as the £150,000 of income relating to the current year estimated RDEC. It will be necessary to deduct £100,000 in the adjustment to profit in the tax computation because this amount was taxed in the earlier year and would otherwise be taxed twice. A further adjustment will be required in the following year if the 31 March 2015 RDEC is settled at an amount other than the estimated £150,000.

As well as tracking the income posted to the statutory accounts it is also important to track any unused elements of the credit that are carried forward because they cannot be used, claimed in cash or surrendered to another group company. The best way to ensure that these amounts are tracked is to include them in a schedule in the tax computation.

Cash flow

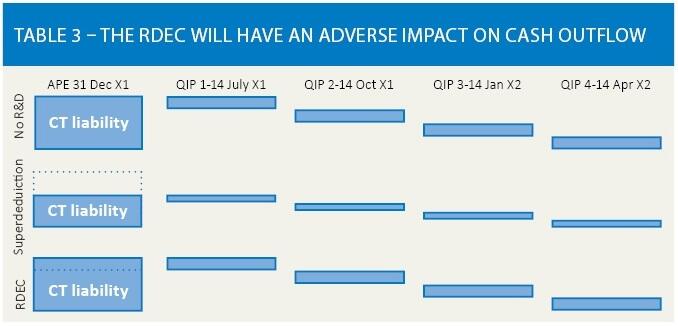

As noted above, the gross RDEC credit is included in the claimant company’s computation of taxable profit, giving rise to an increased corporation tax liability compared to if the company had continued to claim under the super-deduction regime. This will result in a greater cash outflow at the corporation tax payment date, either nine months and one day after the accounting period ends or under the quarterly instalment regime as illustrated in Table 3.

Because the RDEC is a credit that is offset against, rather than a deduction that reduces, the company’s corporation tax liability it is not deducted in the calculation of the quarterly instalment payments. The implications of claiming RDEC on a company’s cash flow position will need to be factored in and a process developed for estimating the likely quantum of the tax credit in advance of the first quarterly instalment payment date so that the additional taxable income it generates can be included. Given that the regime becomes mandatory in less than 12 months, this is a consideration that most claimants will need to think about soon. This will be particularly important for those large corporates that need to manage their investors’ expectations of their cash position.

HMRC have not set a framework for the timing of repayments under the RDEC, either for loss-makers claiming the cash credit or taxpayers that may have settled their corporation tax in advance of submitting their RDEC, resulting in an overpayment. Claimant companies expecting cash from HMRC should contact their customer relationship manager or HMRC R&D specialist unit on how they want RDEC amounts to be treated and expected timings for repayment.

For first-time RDEC claimants, providing information to HMRC to enable them to understand how the credit has been used will be helpful. For example, if the company is due a repayment and the PAYE/NIC cap is not applicable, a note could be included in the tax computation to show that this step has been considered, along with details of why the cap does not apply. Companies operating under a group payment arrangement need to be sure before they contact HMRC about RDEC claims that the arrangement for any particular accounting period has been closed and payments have been allocated to participating organisations, otherwise this will hold up the cash.

Conclusion

Most companies have welcomed the introduction of the RDEC regime, but many have found that the tracking the entries through the tax computations and statutory accounts is more complicated than it would at first appear. This, coupled with the negative impact on cash flow, has led to some companies delaying adoption until the RDEC is compulsory.

Actions to take away

The historic definition of R&D for tax relief continues to apply for the RDEC regime. Companies and their advisers should continue to think as widely as possible about the application of this definition to the R&D activities.

Claimant companies and their advisers should understand the implications of the RDEC on key performance metrics and their financial statements. They should consider developing a real-time basis for capturing costing information relating to the RDEC claim to improve the accuracy of estimates.

Tracking the amount and use or surrender of RDEC through the company’s statutory accounts and its corporation tax computation is important. Clear records should be kept.

Companies should model the impact of RDEC on their quarterly instalment payments and engage in an open dialogue with HMRC on the timing of cash payments due.