Where are we now?

The introduction of the ‘limited cost business’ category for the flat rate scheme moved the goalposts for thousands of scheme users. Two years on, Neil Warren considers if and when the scheme still has a useful purpose for small businesses

Key Points

What is the issue?

The introduction of the ‘limited cost business’ category and its rate of 16.5% eliminated the tax savings previously enjoyed by thousands of FRS users. The article reminds readers about this category and whether the time saving benefits of the scheme are really worthwhile if it means extra VAT is payable.

What does it mean to me?

You might act as adviser for some clients who can still make tax savings with the scheme depending on their trading circumstances. The article highlights five different categories where potential tax savings could be made.

What can I take away?

Consider the impact of MTD for VAT and digital record-keeping that is now relevant to many more businesses and might therefore make the scheme less attractive. It is also important to consider the potential impact of the new reverse charge rules that will take effect in the construction industry on 1 October 2019 because this will affect many builders who use the scheme.

Time flies by very quickly! I can’t believe that two years have passed since the most important date in the history of the flat rate scheme (FRS), when a new category was introduced for a ‘limited cost business’ (LCB) on 1 April 2017. In a nutshell, a 16.5% rate applies to users that spend either less than 2% of their gross sales on goods or £250 in a VAT quarter. This draconian rate has wiped out the financial gains previously enjoyed by thousands of scheme users across the UK, particularly those businesses that sell standard rated services, with not much input tax to claim on their expenses. In many cases, these businesses used to qualify for a favourable rate of 12% for ‘business services not listed elsewhere’. The key question is as follows: Does the FRS still serve a useful purpose for some SMEs? And in this age of easy to use accounting software and apps, are the scheme’s time saving benefits that HMRC promote with such enthusiasm really worthwhile?

Scheme rules

The main principles of the FRS are as follows:

A business chooses its relevant category from a list of 54 activities published via Notice 733, section 4 and applies this percentage to its VAT inclusive business income for the period in question. This calculation includes income from zero-rated and exempt sales but not those that are outside the scope of VAT, e.g. most sales of services to B2B customers based outside the UK are excluded.

A business can claim input tax on capital expenditure goods where the cost of the item exceeds £2,000 including VAT and also pre-registration input tax on its first VAT return after registration, using the same rules as non-scheme users. All other input tax is not claimed.

The scheme can only be adopted by a business that expects its taxable sales excluding VAT to be less than £150,000 in the next 12 months.

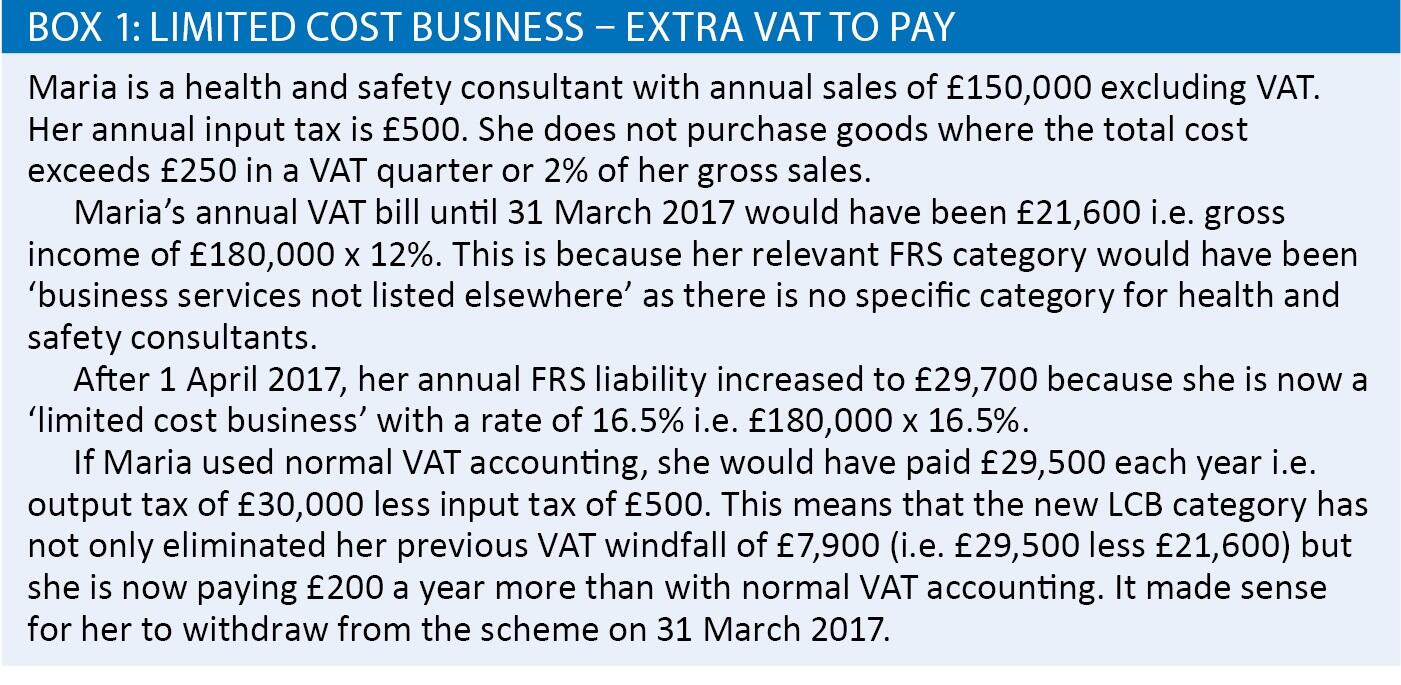

The main outcome of the new LCB category was that it significantly increased the VAT bills of many users, leading to scheme withdrawal in many cases, and deregistration for many businesses that were registered for VAT on a voluntary basis just to enjoy the windfalls. See Box 1: Limited cost business – extra VAT to pay.

Time saving benefits

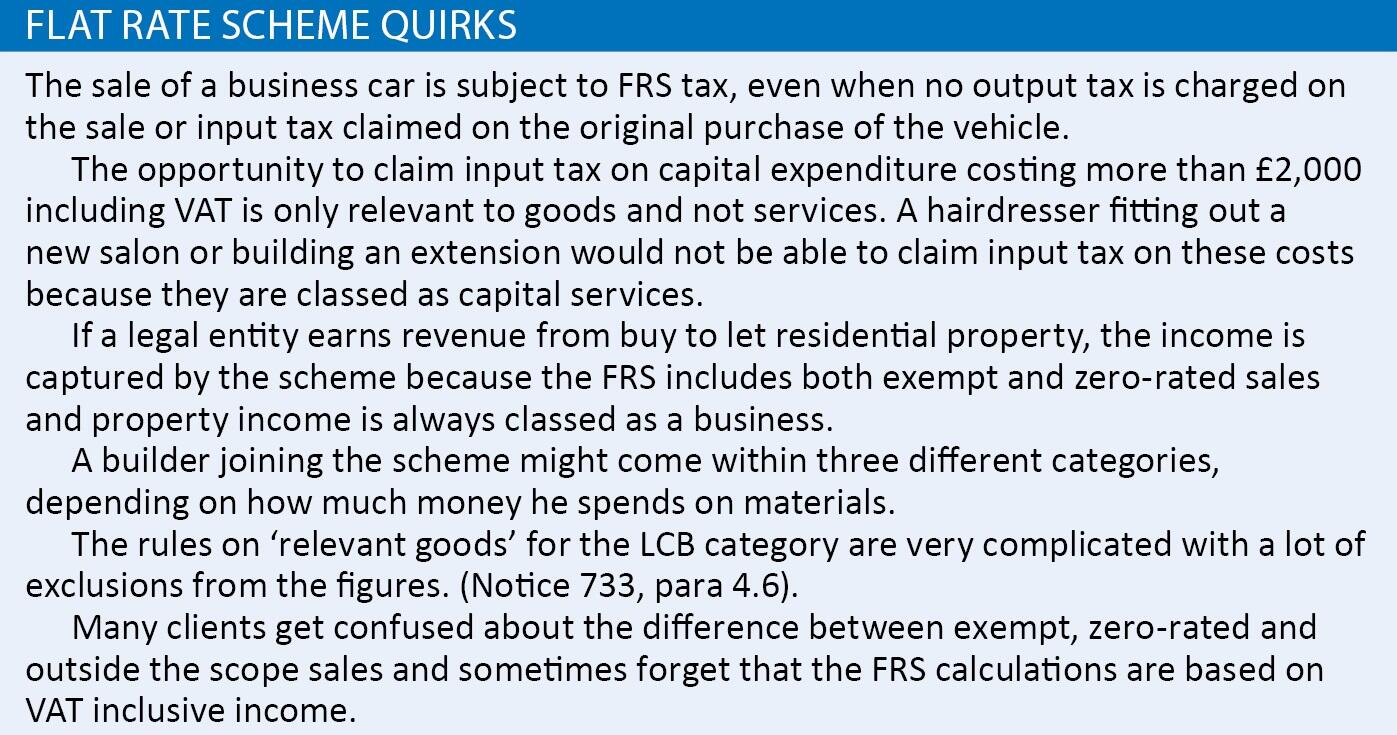

HMRC would argue that the extra £200 of annual VAT paid by Maria is a worthwhile cost because she is still saving time by using the scheme and there is less risk of making errors on her VAT returns. But is this really the case? She still has to record her purchase invoices for direct tax purposes, so the only difference is that she does not need to split her sales and purchase invoices between a ‘net’ and ‘VAT’ breakdown. My counter argument is that there are so many hidden surprises with the FRS that the risk of errors is often higher than with normal VAT accounting. See Flat rate scheme quirks.

In reality, I have never been convinced that clients have lapped up the time saving benefits of the FRS with the same enthusiasm that a dog would lap up a big bowl of water after a run in the park on a hot day. And I think that many clients starting up in business and becoming VAT registered might be more reluctant to join the FRS after the recent introduction of MTD for VAT because the new software packages they will use in many cases are geared to posting sales and purchase invoices and then letting the software work out the VAT return figures ie without manual intervention. Does the business owner really want to muddy the waters by having to consider all of the quirks I listed above? I still think the key issue is whether there are worthwhile tax savings to be enjoyed.

Tax savings

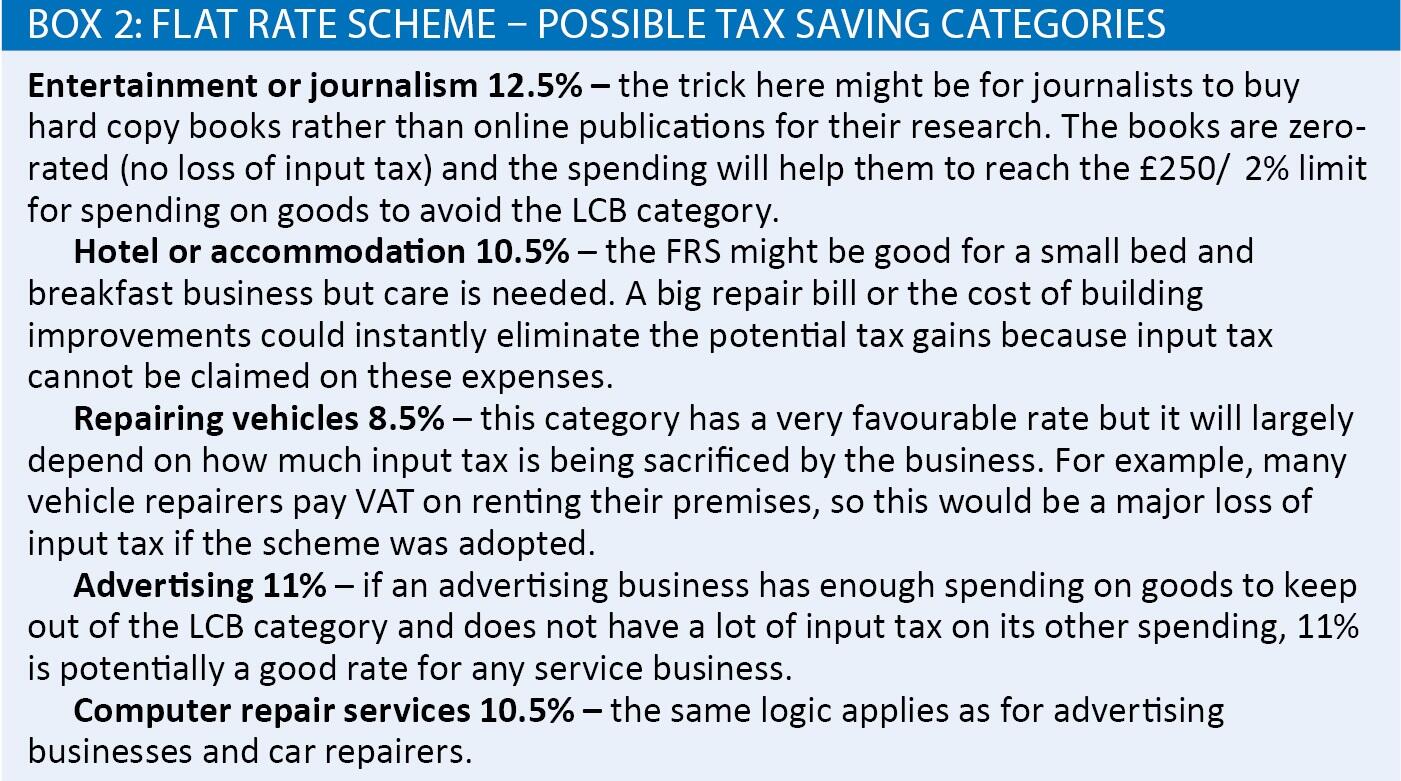

The main challenge is to consider if there are still some categories where the rate is quite generous and joining the scheme could save tax. In other words, are there SMEs that are not affected by the LCB category and their trading circumstances might produce a worthwhile tax saving? See Box 2: Flat rate scheme – possible tax saving categories where I have shown my ‘top five’ suggestions where it could still prove a winner.

New reverse charge rules

As a final tip, be aware that the introduction of the ‘reverse charge’ for construction services on 1 October 2019 will have an impact on many builders who currently use the FRS. The reverse charge will apply to supplies between construction businesses e.g. a subcontractor working for a main building contractor and will mean that the supplier will not charge 20% VAT on his fee (or materials), the customer instead accounting for output tax on his own return. Builders using the FRS will exclude these sales from their VAT returns, so it will be better in most cases for a builder to withdraw from the scheme so that he will be able to claim input tax on his expenses.

Conclusion

When the introduction of the LCB category was imminent back in 2017, I wrote an article for another publication headed ‘FRS–RIP’ predicting the demise of the scheme. This was perhaps a bit dramatic but there has definitely been much less interest about it from both accountants and clients. Another key point is that the annual joining threshold of £150,000 has not changed since April 2003, so this has also squeezed the number of potential users and will continue to do so.

Overall, it is fair to conclude that the tax bonanzas enjoyed by many SMEs between 2003 and 2017 are firmly in the past and will never return. As the old saying goes, all good things come to an end.