A global VAT One Stop Shop: boosting development

We explore how non-EU One Stop Shops could support the digital sector and boost development in emerging and developing economies.

Key Points

What is the issue?

As international VAT systems change to tackle avoidance issues associated with globalisation and digitalisation, digital services businesses are facing increasing numbers of registration requirements. This is preventing some businesses from entering markets due to high compliance costs relative to revenue, impacting development.

What does it mean for me?

While collaboration in Europe has helped to mitigate this issue, similar collaboration has not been seen outside the EU. Registration requirements and the associated administrative costs are likely to continue to rise outside the EU.

What can I take away?

While additional challenges exist outside the EU to achieving something similar to a One Stop Shop that would reduce compliance requirements, there is still an opportunity for increased tax collaboration. This could reduce business costs and increase the supply of services that can support development.

Digitalisation plays a crucial role in supporting development. Digital health services save lives, distant education services improve literacy rates and digital finance promotes financial inclusion. While historically, finance required banks on street corners, healthcare required doctor surgeries and education required schools, digitalisation provides an opportunity for emerging and developing economies to skip this stage of development and create agile societies built on digital infrastructure.

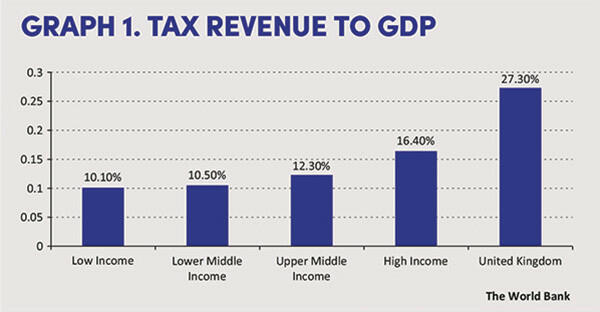

Domestic revenue mobilisation, the process through which governments generate income to fund spending and investment in infrastructure, also supports development, paying for vital services and investment. Graph 1. Tax revenue to GPD details the tax revenue to gross domestic product (GDP) percentage for emerging and developing economies by income classification and the United Kingdom. There is a clear correlation with tax revenue as a proportion of GDP increasing with income levels.

While emerging and developing economies often receive overseas development aid, this is typically less than 50%, 10% and 1% of low income, lower-middle income and upper-middle income country revenues. According to the World Bank, a tax-to-GDP of at least 15% is required to develop rapidly. To meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals (17 goals designed to address poverty, inequality, climate change and injustice), a tax-to-GDP ratio of approximately 20% is needed (see tinyurl.com/yc3nw68w).

Over 86% of low income and 43% of lower-middle income countries fall below this 15% of GDP threshold (see tinyurl.com/3tcyy5nj). Ensuring domestic revenue mobilisation by increasing tax-to-GDP ratios is critical to continued development.

The role of indirect taxes

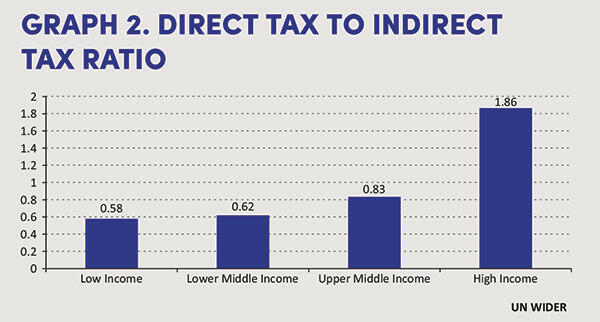

Indirect taxes are crucial to domestic revenue mobilisation in emerging and developing economies. Graph 2. Direct tax to indirect tax ratio shows the direct tax-to-indirect tax ratio by country income levels, with direct-to-indirect tax ratios increasing with income levels (as income increases, direct taxes represent a greater proportion of tax revenue).

High-income countries are still more effective at raising revenue through indirect taxes, largely due to the larger informal economy in emerging and developing economies. The difference in the direct tax-to-indirect tax ratio is primarily driven by a higher-income country’s relative ability to raise revenue through personal income taxes and social security contributions.

Emerging and developing economies have been unable to increase tax revenue from direct tax sources as these taxes relative to indirect taxes typically:

- are more progressive than indirect taxes, leading to political challenges concerning their use;

- require greater administrative capabilities, particularly given that indirect taxes often involve the physical movement of goods that can more easily be traced; and

- cannot be applied to goods with high inelastic demand, like tobacco and alcohol duties.

The VAT digitalisation problem

While the ability to levy indirect taxes on physical goods remains unchanged, the difficulty in levying indirect taxes on digital services means digitalisation has made capturing the entire tax net more difficult. Asia has the largest number of internet users (2.5 billion), having tripled in the past ten years. In Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, internet users have doubled between 2016 and 2021 and 2019 and 2024, respectively (see tinyurl.com/mrk2djjz). Rapid digitalisation has created problems in raising revenue through indirect taxes.

International indirect tax systems are built on traditional business models, where businesses typically have a physical presence in the countries in which they operate. There are some exceptions, such as land-related or transportation services, but historically governments required businesses to charge VAT on services in the country in which they are established. However, businesses providing digital services do not need a presence in a given country to make supplies.

The traditional VAT system is unable to effectively raise revenue on digital services, leading to lost VAT revenue. To tackle this, governments have implemented two rules:

- For supplies by overseas businesses to domestic business customers, the business customer is liable to self-account for local VAT through the reverse charge mechanism.

- Governments have implemented the vendor collection model for cross-border supplies to private customers, where businesses must register and account for VAT in the customer’s jurisdiction.

Overseas businesses are often more complicated to audit and monitor so the vendor collection model is usually complemented with rules to encourage voluntary compliance with mandatory tax obligations, such as simplified VAT returns and less stringent record-keeping requirements. Governments also often exempt businesses that provide services under a given threshold from registering.

The annual revenue benefits of implementing these rules can be as high as 0.1% of GDP. At present, over 100 tax jurisdictions have implemented the vendor collection model. Although some countries offer simplified compliance, these rules significantly increase the administrative burden for businesses due to the increased number of registration requirements.

Shauna Bates, a Senior Manager in EY’s Technology, Media and Telecommunications indirect tax team, said her clients find the number of obligations that they are now facing given the rise of indirect tax rules applicable to digital services to be taking up a significant amount of tax team resource. ‘Our clients are constantly faced with registration portals that are not yet live or hard to access, and the need to produce translated documents or documents that have been legally verified. There is a cost attached to procuring these documents, as well as the cost of the time it takes to coordinate the registration end to end. This can take time away from other indirect tax obligations that a business also needs to deal with.’

One tax leader of a business in The MOSS Group, a European business collective focused on issues regarding VAT compliance and digital services, shared an example of the differing administrative costs related to registering across different jurisdictions. ‘One country required a local SIM card that could only be purchased physically in-store in that country to read security codes to access the country’s tax filing system. Non‑residents could purchase only two of these cards in their lifetime, and fingerprints had to be offered in return for the purchase. Costs like these are hard to quantify but substantial and must significantly impact trade.’

Some businesses choose not to sell digital services to countries where the profit on supplies does not exceed the costs of compliance, which will have an impact on development. One FTSE 350 tax leader said: ‘Increased digital VAT compliance costs alone have prevented us from operating in some markets.’ There are also some companies that enter markets without registering for VAT due to the risk and value of penalties being low.

The EU’s solution

The EU initially tackled this issue by introducing the Mini One Stop Shop. The Mini One Stop Shop allowed businesses to register for VAT in one EU member state and submit one VAT return for all supplies of telecommunication, broadcasting and electronic services sold to private customers. Businesses could report the value of supplies to customers across different EU member states, and the tax authority of registration would remit this VAT to each member state.

As businesses typically do not incur costs in the countries where they make supplies due to a lack of physical presence, input tax (VAT on costs incurred in making supplies) is not recoverable on Mini One Stop Shop returns but is used simply to remit output tax (VAT on services supplied).

The Mini One Stop Shop reduced the administrative burden and costs associated with the vendor collection model, as businesses no longer had to maintain multiple VAT registrations across the EU. Another member of The MOSS Group advised that ‘while not perfect, with problems regarding difficulties reducing VAT liabilities resulting from credit notes and input tax, the Mini One Stop Shop has been revolutionary in reducing compliance costs’.

The EU has made further changes to support digital suppliers through its VAT in the digital age initiative. From 1 July 2021, the Mini One Stop Shop was replaced by the One Stop Shop, expanding the scope of the rules to include all cross-border services to private customers and intra-EU sales of goods.

Towards a global Mini One Stop Shop

Recent years have seen an increase in tax collaboration, both at the international level through organisations like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, OECD and the UN; and at the regional level through organisations like the Asian Development Bank and the African Tax Administration Forum, the most prominent example being OECD’s Two Pillar Solution. These organisations could play a similar role to the EU in facilitating similar simplifications regarding the reporting and remitting VAT on digital supplies. International financial institutions and regional development banks have an important role in building tax capacity in countries to be able to take part and benefit from multilateral revenue generation solutions.

The benefits of a non-EU Mini One Stop Shop for businesses and emerging and developing economies are clear. Businesses may have avoided making supplies in a given jurisdiction where the administrative burden of registering and submitting VAT registrations outweighs profit. Businesses lose out on profits, and emerging and developing economies lose out on digital services and tax revenue, which could be critical to development.

A FTSE 100 tax leader shared their thoughts on the EU One Stop Shop and the benefit that a non-EU One Stop Shop could have on trade and compliance costs. ‘It is unquestionable that the EU One Stop Shop has had a positive impact, reducing compliance costs. If something similar were implemented outside the EU, this could have a significant positive impact on market entry costs.’ A Fortune 500 tax leader agreed, ‘The EU OSS has provided significant simplification benefits, and it would be good to see these replicated elsewhere.’

Despite the benefits, there are additional challenges to achieving something like the One Stop Shop outside the EU. The first is the lack of political power of these organisations to coordinate a multilateral agreement (i.e. a political agreement between more than two countries). While the EU has the political power to issue VAT directives across the EU, the same power does not exist in other regional or international organisations.

Countries would not only need to agree to remit VAT on the behalf of different jurisdictions, but they would also need to agree on the associated fees for doing so, exchange rates, digital infrastructure and security requirements. The time taken and difficulty agreeing to the OECD Pillar Two rules emphasise the challenge of making multilateral tax agreements.

An alternative to agreeing to a multilateral agreement would be for international and regional organisations to facilitate bilateral agreements (a political agreement between just two countries). Different countries could Lego-brick onto existing bilateral agreements, creating a network of bilateral One Stop Shop agreements. International and regional bodies could facilitate this by agreeing on a general set of principles for these bilateral agreements.

Countries may also still require businesses to meet domestic record-keeping requirements, appoint fiscal representatives and subject businesses to audit. If the country of registration holds the audit responsibilities, these audit processes would need to be agreed upon. This is of particular importance given that the nature of digital services makes them difficult to trace. A significant proportion of administrative costs could be reduced by simply having one return, even if definitions remain misaligned, audit and monitoring remain the responsibility of tax authorities in the customer’s jurisdiction, and different record-keeping requirements are maintained.

Providing that tax jurisdictions can agree on security requirements, digital infrastructure, processing fees and exchange rates, there would be an avenue for regional organisations like the Asian Development Bank and the African Tax Administration Forum to facilitate bilateral and multilateral agreements that could lead to a non-EU Mini One Stop Shop. Reducing VAT registrations and obligations could significantly reduce costs for suppliers and boost trade in vital services that are increasingly becoming central to development.

This article represents the author’s own views and not the views of any current or previous employers.