The case of Cooke v HMRC: the problems caused by a rounding error

We consider a case involving a shareholder who claimed entrepreneurs’ relief when he owned 4.99998% of a company’s shares. Does the First-tier Tribunal have the authority to rectify a rounding error?

Key Points

What is the issue?

The case of Cooke v HMRC concerns a claim for entrepreneurs’ relief when the taxpayer owned 4.99998% (rather than the requisite 5%) of the company’s shares. The agreement was based on spreadsheet calculations which showed percentages to two decimal places.

What does it mean to me?

The First-tier Tribunal agreed that it can decide a tax dispute on the assumption that rectification had been granted by the High Court, even without such an application actually having been made.

What can I take away?

If a taxpayer is relying on an equitable remedy, it is probably advisable to put a stay on any enquiry or appeal proceedings and for an application to be made to the High Court, at least until resolution of the scope of the First-tier Tribunal’s jurisdiction.

Entrepreneurs’ relief (now business asset disposal relief) was introduced in the Finance Act 2008 and has survived longer than its predecessor, taper relief. Its conditions have been tinkered with over the years, most importantly an extension in 2019 from one year to two for the period up to the disposal during which the relevant asset (or assets were) had to be owned.

However, despite these occasional changes, the fundamental rules have remained intact. In particular, the general rule applying to disposals of shares in trading companies (for which I also include the holding companies of trading groups) is that the shareholder must have owned at least 5% of the shares for the 12 month or 24 month qualifying period.

The case of Cooke v HMRC [2024] UKFTT 272 (TC) concerns a claim for entrepreneurs’ relief when the taxpayer owned 4.99998% (rather than the requisite 5%) of the company’s shares.

The facts of the case

Mr Cooke was an adviser to the founders of a company, ISG Holdings Ltd. After several years, he agreed to make an investment into the company. Because of his previous experience with entrepreneurs’ relief, Mr Cooke was very keen to secure at least 5% of the company’s shares and he even ensured that the agreement contained an anti-dilution clause, meaning that there was no danger of his shareholding falling below the 5% threshold.

Accordingly, he entered into an agreement which allowed him to purchase 245,802 shares in the company, which the parties thought gave him a 5% stake in the company. Unfortunately, the agreement was based on spreadsheet calculations which showed percentages to two decimal places. Had the calculations been effected without this rounding, it would have become clear that the 245,802 shares amounted to 4.99998% of the company’s share capital.

Therefore, when Mr Cooke claimed entrepreneurs’ relief on the subsequent disposal, HMRC replied by stating that the shares did not qualify for the relief as Mr Cooke’s shareholding was below the threshold.

Mr Cooke appealed against HMRC’s decision and the matter proceeded to the First-tier Tribunal.

The First-tier’s decision

The case came before Judge Sarah Allatt and Mohammed Farooq.

The First-tier Tribunal considered the facts and reached the conclusion that the common intentions of all the parties was to ensure that Mr Cooke retained at least 5% of the shareholding.

HMRC argued that how this would have been achieved was not beyond doubt because a 5% shareholding could have been acquired by Mr Cooke purchasing a single further share but, on the facts of the case, Mr Cooke was shown to have acquired an equal number of shares from each of two of the founding shareholders. However, the tribunal said that these uncertainties were unimportant: what is important is that ‘provided the intended effect is clearly proved, the courts appear to have taken a relatively relaxed approach to the precise terms in which that effect was to be achieved’.

The First-tier Tribunal proceeded to consider whether it had the jurisdiction to give effect to the parties’ intentions; i.e. giving Mr Cooke an assumed 5% shareholding. Ordinarily, the First-tier Tribunal cannot do that but, provided certain conditions are met, the High Court can rectify erroneous documents to reflect the parties’ actual intentions (if not reflected in the written documents) using its equitable jurisdiction.

It was not disputed that the First-tier Tribunal does not have jurisdiction to rectify documents in this way but Mr Cooke argued that the tribunal can decide a tax dispute on the assumption that rectification had been granted by the High Court, even without such an application actually having been made.

The First-tier Tribunal agreed, pointing to the Upper Tribunal’s decision in the case of Joost Lobler v HMRC [2015] UKUT 152 (TCC), which suggested that the First-tier Tribunal could do this provided that it was confident that the High Court would have granted rectification. It must, however, bear in mind that the High Court’s powers are discretionary and will not be exercised if, for example, there has been a delay in the making of an application or an adverse effect on third parties.

Accordingly, the First-tier Tribunal looked at whether the High Court would have granted a rectification in this case. It identified four conditions, as set out by the Court of Appeal in Swainland Builders Ltd v Freehold Properties Ltd [2002] EWCA Civ 560:

- The parties had a common continuing intention, whether or not amounting to an agreement, in respect of a particular matter in the instrument to be rectified.

- There was an outward expression of accord.

- The intention continued at the time of the execution of the instrument sought to be rectified.

- By mistake, the instrument did not reflect that common intention.

The First-tier Tribunal considered that the evidence before it showed that these conditions were met. Furthermore, it saw no reason to believe that the High Court would not exercise its discretion and grant a rectification. In particular, ‘there was little delay in between finding the problem existed and taking some action to remedy this problem and that since then everybody has been on notice that this is something that remains at issue between the parties’.

As there was no material adverse effect on any third party, the First-tier Tribunal could see no reason to suggest that the remedy of rectification would have been refused by the High Court.

For these reasons, the First-tier Tribunal decided the case on the basis that rectification had been granted. Thus, it looked at the case on the basis that Mr Cooke had indeed purchased and retained a 5% shareholding until such time as his shares were sold. Thus, his claim for entrepreneurs’ relief was upheld and the appeal allowed.

Commentary

It is important to stress that the First-tier Tribunal was not suggesting that the 5% threshold can be treated as met if the shareholding was almost but not quite at that level. Parliament has set a condition which is not in itself irrational. Accordingly, even though Mr Cooke’s shareholding was deficient by a single share, amounting to 0.00002% of the company’s share capital (i.e. wholly insignificant from a commercial perspective), he could obtain entrepreneurs’ relief only by running the rectification argument.

Fortunately, for Mr Cooke, he had the facts (and the evidence to prove them) to make it clear that the single share shortcoming was down to a calculation error. It was also fortunate for Mr Cooke that his former co-shareholders were willing to confirm that the minimum 5% shareholding was a shared understanding – although the inclusion of the anti-dilution clause might well have been sufficient to make that point in the absence of other witnesses.

On the facts of the case, it is not difficult to understand why the First-tier Tribunal accepted that this was a case where rectification of the documents was appropriate and where rectification would have been granted by the High Court. However, what I think will be the more significant aspect of the case is the fact that the First-tier Tribunal accepted that it had jurisdiction to determine the appeal as if rectification had been granted by the High Court.

I fully acknowledge that the Upper Tribunal (whose decisions are binding on the First-tier Tribunal) reached the same conclusion in Lobler (see my article ‘Joost busters’ in the June 2015 issue of Tax Adviser). Furthermore, I do not think that the Upper Tribunal was necessarily wrong and it did pave the way to a more streamlined litigation process which cannot be contrary to any policy.

However, as I noted in that article on the Lobler case, ‘some commentators … have suggested that the tribunal’s reasoning … is rather unorthodox’. Because of the facts of the Lobler case, it is not entirely surprising that HMRC chose not to appeal against the Upper Tribunal’s decision to the Court of Appeal. However, it remains unclear whether it has fully accepted that a tribunal can determine an appeal based on only a hypothetical rectification or whether it generally requires taxpayers to make a formal application first to the High Court so that the tax authorities (HMRC and the tribunals) can decide the case in the light of any rectification granted.

Accordingly, it has generally been advisable for taxpayers and HMRC to put a hold on any enquiries or any appeal process and await the outcome of a rectification application to the High Court. On the other hand, such proceedings are not cheap and it would be generally more cost-effective to go straight to the First-tier Tribunal. That latter approach has the advantage of simplicity but always carries the risk that HMRC would dispute the right of the First-tier Tribunal to proceed as the tribunal has done in this case.

Without wishing to add to Mr Cooke’s worries, I do think that this is a case where it would be helpful for HMRC to take the case to the Upper Tribunal so that further clarification can be given to this important issue. (An even better, but less likely, alternative would be for Parliament to make it clear that the First-tier Tribunal’s jurisdiction extends to giving effect to hypothetical rectifications (and other equitable remedies) without conferring jurisdiction on the tribunal to effect such rectifications.

Of course, if HMRC chooses not to appeal against the First-tier Tribunal’s decision in the Cooke case, it would seem that it is content with the tribunal’s approach, but it would be helpful if the professional bodies could get a clear statement from HMRC to this effect.

For the sake of completeness, it is possible that there is one minor omission in the First-tier Tribunal’s decision. The tribunal’s decision was predicated on the assumption that Mr Cooke had acquired at least one further share so as to take him across the 5% threshold and, indeed, the tribunal recognised that (had rectification been granted by the High Court) Mr Cooke would be owed the sale proceeds for that further share from another shareholder.

On this basis, it appears that Mr Cooke’s disposal proceeds should have been treated as increased by the value of that further one share and capital gains tax paid on those additional proceeds, albeit at the rate of 10%. Strictly speaking, therefore, the closure notice should have been adjusted not simply to reinstate the entrepreneurs’ relief but also to show the additional capital gains tax payable on that single further share.

As I have said, however, it is a minor point and it is possible that the difference it makes is so insignificant that it did not need to be addressed in the decision. It is also possible that the tribunal was looking only at the principles and therefore it did not need to address the minutiae of the actual tax payable.

What to do next

If a taxpayer is relying on an equitable remedy, it is probably still appropriate to put a stay on any enquiry or appeal proceedings and for an application to be made to the High Court, at least until resolution of any ongoing doubts as to the scope of the First-tier Tribunal’s jurisdiction.

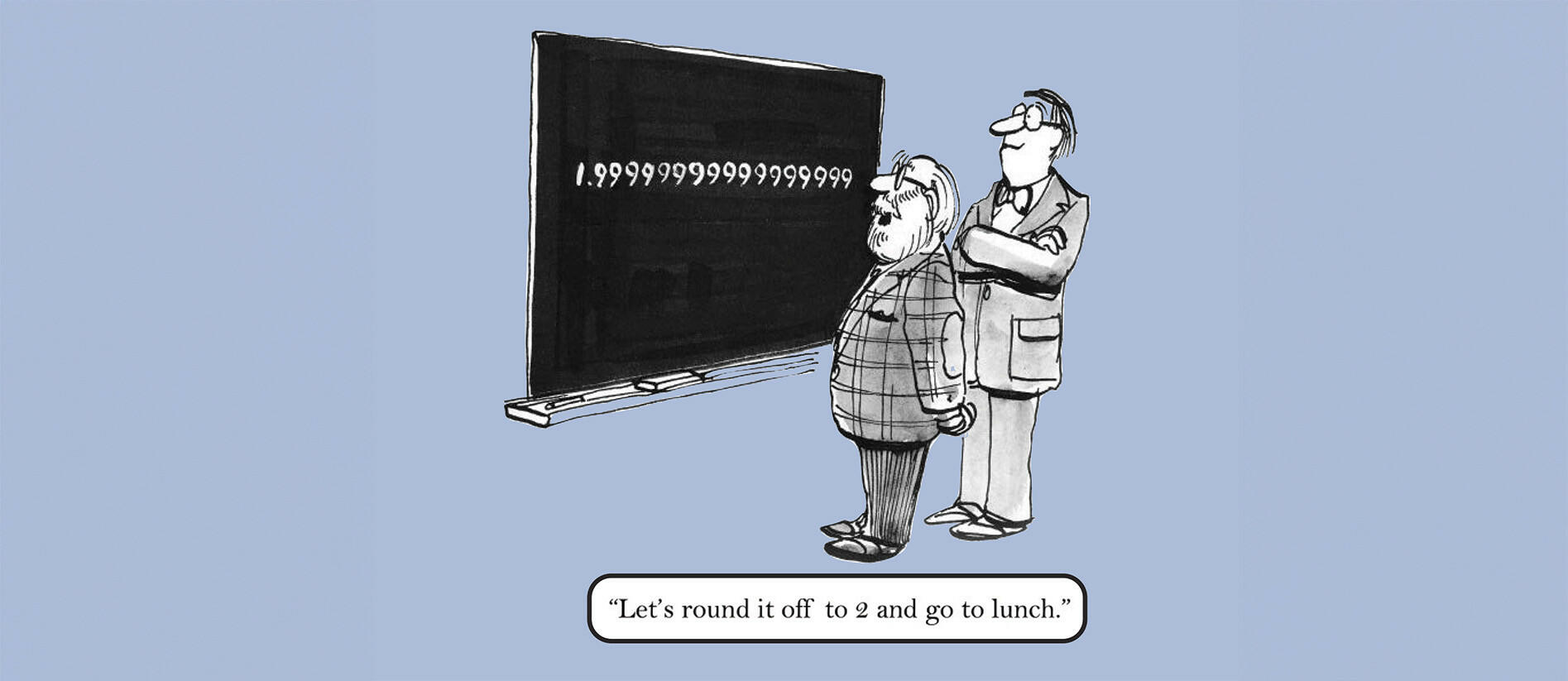

More generally, the case is a reminder that rounding in spreadsheets is very common. When cliff-edge thresholds are encountered, it is essential to double check calculations to ensure that a potentially catastrophic error has not been introduced by any rounding process. Though this may look like madness, there is method in it.